Hummingbirds have long enchanted us with their vibrant colors, dazzling flight abilities, and solitary feeding behaviors. However, emerging research is challenging the traditional view of these birds as solitary creatures. Scientists are uncovering surprising aspects of hummingbird social behavior, particularly in species like the Chimborazo hillstar (Oreotrochilus chimborazo), which exhibit communal nesting and coordinated group movements. This blog post explores these fascinating discoveries, shedding light on the social dynamics of hummingbirds and their implications for avian biology.

Hummingbird Social Behavior: Not So Solitary After All

Traditionally, hummingbirds have been viewed as solitary creatures, fiercely defending their territories and rarely engaging in social interactions beyond mating. However, recent discoveries are challenging this long-held belief, revealing a more complex social structure than previously thought.

Colonial Nesting: A Groundbreaking Discovery

The Chimborazo Hillstar’s Communal Lifestyle

The Chimborazo Hillstar (Oreotrochilus chimborazo), a hummingbird species native to Ecuador’s high-altitude Andes, has recently captured global scientific attention due to its unexpected communal nesting behavior. This groundbreaking discovery challenges the long-standing perception of hummingbirds as solitary and fiercely territorial creatures.

Unveiling the Discovery

In a remote mountain cave on the slopes of Chimborazo volcano, researchers observed approximately 30 Chimborazo Hillstars nesting and roosting together—a behavior never before documented in hummingbirds. These birds, typically known for their aggressive territoriality, were found building nests in close proximity, with males, reproductive females, and non-reproductive females all sharing the same space. This communal nesting arrangement starkly contrasts with the solitary nesting habits typical of most hummingbird species.

Environmental Pressures and Adaptation

The harsh environment of the high Andes likely played a significant role in driving this behavior. The Chimborazo Hillstars inhabit altitudes above 12,000 feet, where extreme cold, high winds, and limited resources such as nectar-rich flowers and safe nesting sites make survival particularly challenging. The cave environment offers a stable microclimate and protection from predators, providing a critical advantage for these birds in such an unforgiving habitat.

Initially, researchers hypothesized that limited availability of suitable nesting sites forced the birds to aggregate. However, further studies revealed that solitary nesting sites were available but underutilized. This finding suggests that the birds may derive additional benefits from communal living beyond mere shelter. Potential advantages include increased reproductive success, better access to mates and food resources through information exchange, and enhanced protection against environmental threats.

Evolutionary Implications

The discovery has significant implications for understanding the evolution of social behavior in birds. While coloniality is common in some bird species like penguins or swallows, it is virtually unheard of in hummingbirds. Researchers speculate that once Chimborazo Hillstars began congregating due to environmental pressures, they may have developed traits that enhanced social interactions and cooperation over time. These traits could include coordinated group movements or shared defense mechanisms against predators.

Future Research Directions

This finding opens new avenues for studying how extreme environments influence social behavior in birds. Researchers aim to investigate whether similar communal behaviors exist in other hummingbird species or if this phenomenon is unique to the Chimborazo Hillstar. Additionally, understanding the genetic and ecological factors underlying this adaptation could provide deeper insights into how species evolve cooperative strategies under environmental stress.

In summary, the Chimborazo Hillstar’s communal lifestyle not only redefines our understanding of hummingbird behavior but also highlights the remarkable adaptability of life in extreme conditions. This discovery underscores the importance of continued research into avian ecology and evolution to uncover nature’s hidden complexities.

Group Dynamics: Coordinated Movements

Beyond colonial nesting, researchers have observed other intriguing social behaviors in hummingbirds. In several species, including the green

hermit (Phaethornis guy) and the rufous-tailed hummingbird (Amazilia tzacatl), individuals have been seen departing from and returning to roosting sites as a group.

These coordinated movements suggest a level of social cohesion previously unrecognized in hummingbirds. The birds appear to synchronize their activities, possibly as a strategy to reduce predation risk or improve foraging efficiency. This behavior raises questions about the mechanisms of communication and decision-making in hummingbird groups.

Furthermore, some species have been observed engaging in what appears to be cooperative defense against predators. In these instances, multiple hummingbirds will mob potential threats, such as larger birds or small mammals, working together to drive them away from nesting or feeding areas.

These observations of group dynamics challenge the traditional view of hummingbirds as strictly solitary creatures. They suggest that, at least in some contexts, hummingbirds are capable of and benefit from social interactions and cooperative behaviors.

The implications of these findings extend beyond hummingbird biology. They provide valuable insights into the evolution of social behavior in birds and the ecological factors that may drive the development of cooperative strategies in seemingly unlikely species.

Behavioral Adaptations to Human Activity: Urban Hummingbirds

As human populations expand and urban areas grow, many animal species face challenges adapting to these altered environments. Hummingbirds, however, have shown remarkable flexibility in adjusting their behaviors to human presence and activity.

Weekly Activity Cycles: Adapting to Human Rhythms

A fascinating study on broad-tailed hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus) in agricultural areas revealed that these birds adjust their territorial and feeding behaviors based on human activity levels. Researchers observed that during weekdays, when human presence and activity in the area were higher, the hummingbirds reduced their defensive behaviors and altered their feeding patterns.

Specifically, the hummingbirds were found to spend less time defending their territories and more time feeding during periods of increased human activity. This behavioral shift likely represents an energy-saving strategy, as constant territorial defense in the presence of frequent human disturbances would be energetically costly.

On weekends, when human activity in the area decreased, the hummingbirds reverted to more typical territorial and feeding behaviors. This weekly cycle of behavioral adaptation demonstrates the birds’ ability to fine-tune their activities in response to predictable patterns of human presence.

This research has important implications for understanding how wildlife adapts to human-dominated landscapes. It suggests that some species, like hummingbirds, may be capable of developing nuanced responses to human activity patterns, potentially increasing their chances of survival in anthropogenic environments.

Urban Ecology: Thriving in City Landscapes

The impact of urbanization on hummingbird behavior and ecology is an emerging field of study that offers insights into these birds’ adaptability and conservation needs. Contrary to expectations, many hummingbird species appear to thrive in urban and suburban environments, taking advantage of the resources these areas provide.

Urban hummingbirds have been observed utilizing a wide range of artificial food sources, including nectar feeders and ornamental flowers in gardens. These reliable food sources may allow hummingbirds to expand their ranges into areas that would otherwise be unsuitable, potentially altering their migration patterns and population dynamics.

Research has shown that some hummingbird species, such as Anna’s hummingbird (Calypte anna) in North America, have significantly expanded their range northward, likely due in part to the availability of feeders and suitable plants in urban areas. This range expansion has implications for hummingbird conservation and may affect interactions with other species in these new environments.

Urban hummingbirds also face unique challenges, including collisions with windows, exposure to pesticides, and competition with non-native species. Understanding how hummingbirds navigate these challenges and adapt to urban ecosystems is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies in human-dominated landscapes.

Advanced Cognitive Abilities: Tiny Birds with Big Brains

Despite their small size, hummingbirds possess cognitive abilities that rival those of much larger birds. Recent research has uncovered surprising aspects of hummingbird intelligence, challenging our understanding of brain size and cognitive capacity in birds.

Observational Learning: Social Knowledge Transfer

One of the most intriguing discoveries in hummingbird cognition is their capacity for observational learning. Studies have shown that hummingbirds can learn about novel food sources more quickly and efficiently when they observe the behavior of knowledgeable conspecifics.

In experiments, naive hummingbirds were found to locate and access artificial feeders more rapidly when they could observe experienced individuals feeding from these sources. This social learning ability suggests that hummingbirds are capable of acquiring and using information from their peers, a cognitive skill previously thought to be limited to larger-brained animals.

The implications of this finding are significant. It suggests that hummingbirds may have more complex social cognitive abilities than previously recognized, potentially influencing their foraging strategies, territorial behaviors, and adaptation to new environments.

Memory and Navigation: Spatial Cognition in a Tiny Package

Hummingbirds demonstrate remarkable spatial memory and navigation skills, abilities that are crucial for their survival given their high-energy lifestyle and the need to locate scattered food sources.

Research has shown that hummingbirds can remember the locations of hundreds of flowers within their territory, and they can time their visits to coincide with the replenishment of nectar in these flowers. This requires not only excellent spatial memory but also an understanding of temporal patterns – a sophisticated cognitive ability.

In one study, rufous hummingbirds (Selasphorus rufus) were found to remember the location of artificial feeders they had visited only once, even after an absence of several months. This long-term spatial memory is particularly impressive given the birds’ tiny brain size.

Furthermore, hummingbirds appear to use a variety of cues for navigation, including visual landmarks, the position of the sun, and possibly even Earth’s magnetic field. Their ability to integrate these different sources of information to navigate effectively over long distances during migration is a testament to their cognitive sophistication.

These cognitive abilities challenge the notion that brain size is the primary determinant of intelligence in animals. Hummingbirds demonstrate that even a tiny brain can support complex cognitive processes when evolutionary pressures favor such abilities.

Unique Physiological Adaptations: Marvels of Miniaturization

Hummingbirds have evolved a suite of extraordinary physiological adaptations that allow them to thrive in their ecological niche. These adaptations push the boundaries of what’s possible in vertebrate physiology and offer insights into the extremes of animal function.

Torpor Mechanisms: Surviving on the Edge

One of the most fascinating physiological adaptations of hummingbirds is their ability to enter a state of torpor, a controlled reduction of body temperature and metabolic rate. This adaptation is crucial for surviving cold nights and periods of food scarcity, allowing hummingbirds to conserve energy when resources are limited.

During torpor, a hummingbird’s body temperature can drop from its normal 40̊C (104̊F) to as low as 18̊C (64̊F). Their heart rate slows dramatically, from over 1,000 beats per minute during active flight to as few as 50 beats per minute. Breathing rate also decreases significantly.

Interestingly, some hummingbird species have been observed hanging upside-down during torpor, a behavior that has puzzled researchers. Recent studies suggest that this inverted position might help the birds conserve even more energy by reducing the effort needed to grip the perch.

The ability to enter and exit torpor rapidly is a remarkable feat of physiological control. Hummingbirds can rewarm and become active within minutes, allowing them to respond quickly to changing environmental conditions or threats.

Research into hummingbird torpor mechanisms has implications beyond ornithology. Understanding how these birds regulate their metabolism so precisely could provide insights into mammalian hibernation.

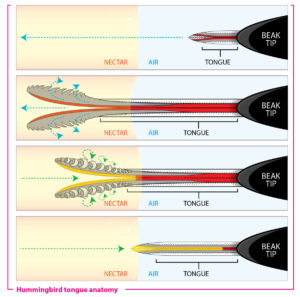

Tongue Structure and Function: Nature’s High-Speed Pump

Hummingbird tongues are marvels of biological engineering, perfectly adapted for their nectar-feeding lifestyle. Recent high-speed video analysis has revealed that the mechanics of hummingbird feeding are far more complex than previously thought.

Contrary to earlier beliefs that hummingbirds used capillary action to draw up nectar, research has shown that their tongues function more like elastic micropumps. The tongue has two grooves that are collapsed and flattened when inside the bill. When extended into nectar, these grooves spring open, allowing fluid to flow in.

As the tongue is withdrawn, the grooves close trapping the nectar inside. This cycle can be repeated up to 20 times per second in some species, allowing hummingbirds to consume nectar at an incredibly rapid rate.

The structure of the hummingbird tongue is unique among vertebrates. It’s composed of two long, thin tubes fused together, with their tips separated into multiple thin, hair-like structures called lamellae. This design allows for maximum nectar collection efficiency while minimizing the energy required for feeding.

Understanding the mechanics of hummingbird tongues has inspired biomimetic research, with potential applications in the design of micro-fluidic devices and efficient liquid-trapping mechanisms.

Behavioral Ecology in Changing Environments: Adapting to a Shifting World

As global environments undergo rapid changes due to human activities and climate change, understanding how hummingbirds respond to these shifts is crucial for their conservation and for predicting future ecological dynamics.

Impact of Climate Change: Shifting Phenologies and Range Expansions

Climate change is altering the timing of seasonal events (phenology) in many ecosystems, potentially creating mismatches between hummingbirds and their food sources. Research is ongoing to understand how shifting flowering times and nectar availability due to climate change affect hummingbird migration and breeding patterns.

Some studies have found that certain hummingbird species are adjusting their migration timing in response to earlier spring conditions. For

example, ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) have been observed arriving at their breeding grounds earlier in recent years, correlating with earlier onset of spring in these areas.

However, not all plant species are shifting their flowering times at the same rate, which could lead to temporal mismatches between hummingbirds and their preferred nectar sources. This potential mismatch is a significant concern for hummingbird conservation, as it could affect their ability to find sufficient food during critical periods of their annual cycle.

Climate change is also driving range expansions in some hummingbird species. Anna’s hummingbirds, for instance, have expanded their range northward along the Pacific coast of North America, likely due to milder winters and increased availability of food sources in urban areas.

These range expansions can have cascading effects on ecosystems, potentially altering plant-pollinator relationships and competitive interactions with other species. Monitoring these changes and understanding their ecological implications is crucial for predicting future biodiversity patterns and developing effective conservation strategies.

Adaptation to Novel Food Sources: Urban Ecology and Non-Native Plants

As human-altered landscapes become increasingly prevalent, hummingbirds are adapting to utilize novel food sources, including artificial nectar feeders and non-native plant species in urban and suburban environments.

Artificial nectar feeders have become a common feature in many areas, providing a reliable food source for hummingbirds. While these feeders can support hummingbird populations, especially during periods of natural food scarcity, they also raise questions about potential impacts on hummingbird behavior, health, and ecological relationships.

Research has shown that hummingbirds can become dependent on feeders, altering their foraging patterns and potentially affecting their role as pollinators in natural ecosystems. There are also concerns about the spread of diseases at feeders, highlighting the need for proper feeder maintenance and monitoring.

Non-native plant species in urban and suburban gardens present both opportunities and challenges for hummingbirds. Many exotic ornamental plants provide abundant nectar, potentially supporting hummingbird populations in areas where native food sources are scarce. However, these plants may not provide the same nutritional quality as native species, and their presence could alter local plant-pollinator networks.

Studies on hummingbird foraging preferences in urban environments have found that while hummingbirds will readily visit non-native flowers, they often show a preference for native species when available. This suggests that maintaining native plant diversity in urban and suburban landscapes is important for supporting healthy hummingbird populations.

Understanding how hummingbirds adapt to and utilize these novel food sources is crucial for urban ecology and conservation planning. It can inform strategies for creating hummingbird-friendly urban environments and help mitigate potential negative impacts of urbanization on these important pollinators.

In conclusion, these five areas of emerging hummingbird research – social behavior, adaptation to human activity, cognitive abilities, physiological adaptations, and responses to changing environments – are reshaping our understanding of these remarkable birds. By delving into these topics, researchers are uncovering the hidden complexities of hummingbird biology and ecology, offering new insights that can inform conservation efforts and deepen our appreciation for these tiny marvels of nature.

As we continue to study hummingbirds, we are likely to discover even more surprising aspects of their lives, challenging our preconceptions and expanding our knowledge of what’s possible in the natural world. For those seeking to become authorities on hummingbirds, staying abreast of these emerging areas of research will be crucial in developing a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of these fascinating creatures.

If you found this article helpful please share it with your friends using the social bookmarking buttons on the left side of this page. Help everyone to increase their enjoyment of feeding hummingbirds. Do it for the hummingbirds!

Valuable Hummingbird Information To Increase Your Enjoyment

Here’s a complete guide to attracting hummingbirds to your yard. It lists plants, vines and shrubs that are in bloom for spring, summer and fall. Your hummingbirds will always have flowers to feed on.

Here’s a great article that tells everything you need to know about how to choose the best place to hang your hummingbird feeder.

Here’s the best designed hummingbird feeder to use. It’s leak proof, so it won’t attract insects and it’s easy to take apart and clean.

Here’s a comprehensive guide to help you clean your hummingbird feeder for those times when the nectar is not changed soon enough and mold starts to grow.

One of the best Hummingbird feeders that’s easy to take apart and clean is the HummZinger Ultra.

Aspects 12oz HummZinger Ultra With Nectar Guard.

The HummZinger Ultra 12oz Saucer Feeder is one of the best options for a hummingbird feeder that’s both easy to clean and maintain. This top-tier feeder features patented Nectar Guard tips—flexible membranes on the feeding ports that keep flying insects out while still allowing hummingbirds to feed freely. Plus, it comes with an integrated ant moat to prevent crawling insects from reaching the nectar, and the raised flower ports help divert rain, keeping the nectar fresh.

With a 12 oz capacity, this mid-size feeder offers plenty of space and can be hung or mounted on a post using the included hardware. It has four feeding ports and is made from durable, unbreakable polycarbonate. Whether you’re concerned about bees, wasps, or ants, this feeder is built for easy cleaning and insect protection.

If you already have a hummingbird feeder, and you want to protect it from ants and other crawling insects, the ant moat below will do the job.

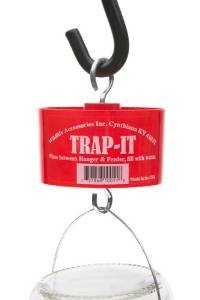

Trap-It Ant Moat for Hummingbird Feeders

Using an ant moat for your hummingbird feeder is an effective way to keep ants away from the sweet nectar. These tiny creatures are drawn to

the sugar water, and without a barrier, they will quickly infest your feeder, preventing the birds from enjoying the nectar. An ant moat works by creating a barrier of water that ants can’t cross. Positioned above the feeder, it effectively blocks the ants’ path, keeping them from reaching the nectar.

This simple solution also ensures that your hummingbird feeder remains clean and accessible for the birds, rather than becoming a breeding ground for ants or other pests. It’s a small addition that can make a big difference in maintaining a healthy, inviting space for hummingbirds, while also reducing the need for chemical ant deterrents.

The first and still the best to protect your Hummingbird and Oriole feeder from ants and other crawling insects. Insert between hanger and feeder and fill with water, providing a barrier to crawling pests. Red color to attract hummingbirds.

| Small bottle brushes and pipe cleaners are always helpful to dislodge mold inside the feeder and in the feeding ports. It is necessary to have a clean mold free feeder to attract hummingbirds and to keep them healthy. |

If you found this article helpful please share it with your friends using the social bookmarking buttons on the left side of this page. Help everyone to increase their enjoyment of feeding hummingbirds. Do it for the hummingbirds!

Hummingbird Resources

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Hummingbird Conservation

This site offers detailed information about various hummingbird species, their habitats, and conservation efforts. It also provides resources on how to protect these fascinating birds.

National Park Service – Hummingbird Resources

The National Park Service offers insights into hummingbird species found in national parks, their behaviors, and their role in ecosystems, along with tips for observing them.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History – Birds: Hummingbirds

This resource provides educational materials on the role of hummingbirds in pollination and biodiversity, backed by scientific research and exhibits from the Smithsonian.

U.S. Geological Survey – Hummingbird Studies

The USGS offers research on hummingbird migration patterns, population dynamics, and environmental threats, including studies on climate change impacts.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology – Hummingbirds

While not strictly a government site, Cornell partners with federal agencies to provide valuable scientific insights into hummingbird behavior, conservation, and field guides.

—