Allen’s Hummingbird (Selasphorus sasin) is a captivating and energetic species that has captured the hearts of bird enthusiasts and nature lovers along the West Coast of North America. Known for its vibrant colors and acrobatic flight, this tiny bird plays a crucial role in the coastal ecosystems of California and southern Oregon. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the fascinating world of Allen’s Hummingbird, from its distinctive characteristics and behavior to its habitat preferences and conservation status.

Physical Characteristics of Allen’s Hummingbird

Size and Appearance

Allen’s Hummingbird is a small but mighty creature, measuring just 3.5 inches (9 cm) in length and weighing a mere 2-4 grams. Despite its diminutive size, this hummingbird species stands out with its striking appearance. The bird’s most notable features include:

-

A copper-green back that shimmers in the sunlight

-

Rust-colored flanks that contrast beautifully with its green plumage

-

An iridescent throat (gorget) that appears red or orange depending on the angle of light

-

A straight, slender bill perfect for probing flowers for nectar

The wingspan of Allen’s Hummingbird typically ranges from 4.3 to 4.7 inches (11-12 cm), allowing for incredible maneuverability and the ability to hover with precision.

Male vs. Female Differences

As with many bird species, there are noticeable differences between male and female Allen’s Hummingbirds:

Male:

-

Brilliant iridescent reddish-orange gorget

-

More vibrant overall coloration

-

Green back with coppery overtones

-

Rufous (reddish-brown) tail feathers and flanks

Female:

-

Lacks the bright gorget, instead having a speckled throat

-

Generally duller in color with more green on the back

-

White-tipped tail feathers

-

Paler rufous wash on the flanks

These differences play a crucial role in mate selection and territorial behavior, which we’ll explore further in later sections.

Habitat and Distribution

Geographic Range

Allen’s Hummingbird has a relatively limited range compared to some other hummingbird species. Its primary distribution includes:

-

Coastal California, from the Oregon border south to Santa Barbara

-

Channel Islands off the coast of southern California

-

A small breeding population in southern Oregon

Interestingly, Allen’s Hummingbird can be divided into two subspecies:

-

S. s. sasin: The migratory subspecies that breeds along the California coast and winters in Mexico.

-

S. s. sedentarius: The non-migratory subspecies found year-round on the Channel Islands and parts of the Los Angeles basin.

Preferred Environments

These hummingbirds show a strong preference for specific habitats, which include:

-

Coastal scrub: Low-growing, drought-resistant shrubs common along the California coast

-

Chaparral: Dense, woody shrubs adapted to dry summers and mild, wet winters

-

Urban gardens: Particularly those with native flowering plants

-

Riparian areas: Zones along rivers and streams with abundant vegetation

Key plant species in their habitat include:

-

California fuchsia (Epilobium canum)

-

Sticky monkey flower (Diplacus aurantiacus)

-

Sage species (Salvia spp.)

-

Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.)

-

Gooseberry and currant (Ribes spp.)

These plants not only provide nectar but also attract small insects that form an essential part of the hummingbird’s diet.

Behavior and Lifestyle

Feeding Habits

Allen’s Hummingbirds are nectar feeders, but their diet is more diverse than many people realize:

Nectar:

-

Primary energy source, providing quick-burning carbohydrates

-

Obtained from a variety of flowering plants, with a preference for tubular flowers

-

Can consume up to half their body weight in nectar daily

Insects and Spiders:

-

Essential source of protein, especially during breeding season

-

Caught on the wing or gleaned from leaves and bark

-

Include small flies, gnats, and spiders

Feeding Technique:

-

Hovers in front of flowers, inserting long bill and extendable tongue to extract nectar

-

Can fly forwards, backwards, and even upside down to access nectar

-

Visits hundreds of flowers daily to meet energy requirements

Breeding and Nesting

The breeding season for Allen’s Hummingbird typically begins in December for the sedentary population and February for the migratory group, extending through June.

Courtship Display:

-

Males perform spectacular dive displays, climbing up to 100 feet before plummeting towards the ground

-

The dive produces a distinctive buzz sound created by air rushing through the bird’s tail feathers

-

These displays serve to attract females and ward off competing males

Nesting:

-

Females are solely responsible for nest building and chick-rearing

-

Nests are tiny cups made of plant down, spider silk, and lichen, often placed on thin branches or vines

-

Usually two eggs are laid, each about the size of a coffee bean

-

Incubation lasts 17-22 days, with chicks fledging after 21-25 days

Territorial Behavior

Allen’s Hummingbirds are known for their aggressive territorial behavior:

-

Males fiercely defend feeding and nesting areas from other hummingbirds and even larger birds

-

Territorial displays include aerial chases, vocalizations, and threat postures

-

Females also defend small territories around their nests

-

This behavior ensures access to crucial nectar sources and nesting sites

Interactions with other species:

-

Often compete with Anna’s Hummingbirds and Rufous Hummingbirds in areas of overlapping range

-

May chase away much larger birds perceived as threats

Identification Tips

Distinguishing Features

To accurately identify Allen’s Hummingbird in the field, look for these key characteristics:

-

Small size, even compared to other hummingbirds

-

Copper-green back contrasting with rufous flanks

-

Males: bright reddish-orange gorget that appears dark when not catching the light

-

Straight, slender bill

-

Rapid wing beats, even for a hummingbird (up to 80 beats per second)

Comparison with Similar Species

Allen’s Hummingbird is often confused with the Rufous Hummingbird due to their similar appearance. Here’s how to distinguish them:

Allen’s Hummingbird:

-

Green back with copper tones

-

Rufous color restricted to flanks and base of tail

-

Slightly smaller overall

Rufous Hummingbird:

-

More extensive rufous coloring, often covering most of the body

-

Green restricted to the back and crown

-

Slightly larger than Allen’s

Vocalizations

Allen’s Hummingbirds have a variety of vocalizations:

-

Common call: a sharp, metallic “chip” or “tik” sound

-

Song: a series of high-pitched squeaks and buzzes, often given during courtship displays

-

Wing sounds: distinctive buzzing produced during courtship dives

These vocalizations serve multiple purposes:

-

Territorial defense

-

Communication between mates

-

Warning calls when predators are nearby

Conservation Status and Threats

Population Trends

Currently, Allen’s Hummingbird is not considered endangered, but it is a species of special concern:

-

Population estimates vary, but numbers are believed to be declining

-

The IUCN Red List categorizes it as “Least Concern” due to its relatively large range

-

However, some studies suggest a decline of up to 2% annually in recent years

Factors Affecting Population

Several factors contribute to the challenges faced by Allen’s Hummingbird:

-

Habitat Loss: Urban development along the California coast has reduced available breeding and feeding areas.

-

Climate Change: Shifting weather patterns may affect the timing of flower blooms and insect availability, potentially disrupting the hummingbird’s feeding and breeding cycles.

-

Non-native Plants: The spread of invasive plant species can alter the composition of native plant communities that Allen’s Hummingbirds rely on.

-

Window Collisions: As with many bird species, collisions with windows in urban and suburban areas can be a significant source of mortality.

Conservation Efforts

Several initiatives are underway to protect Allen’s Hummingbird and its habitat:

-

Habitat Preservation: Conservation organizations are working to protect and restore coastal scrub and chaparral habitats.

-

Native Plant Programs: Efforts to promote the use of native plants in landscaping benefit Allen’s Hummingbirds and other pollinators.

-

Research and Monitoring: Ongoing studies track population trends and habitat use to inform conservation strategies.

-

Public Education: Programs aimed at increasing awareness about the importance of hummingbirds and their conservation needs.

How to Attract Allen’s Hummingbirds to Your Garden

Creating a hummingbird-friendly garden can provide crucial resources for Allen’s Hummingbirds and offer excellent opportunities for observation.

Plant Selection

Focus on native plants that Allen’s Hummingbirds naturally seek out:

-

California fuchsia (Epilobium canum)

-

Sticky monkey flower (Diplacus aurantiacus)

-

Sage species (Salvia spp.)

-

Columbine (Aquilegia formosa)

-

Western coral bean (Erythrina speciosa)

Aim for a variety of plants that bloom at different times to provide a consistent nectar source throughout the season.

Here’s a complete guide toattracting hummingbirds to your yard. It lists plants, vines and shrubs that are in bloom for spring, summer and fall. Your hummingbirds will always have flowers to feed on.

Feeder Tips

While natural nectar sources are ideal, feeders can supplement a hummingbird’s diet:

-

Use feeders with red parts, as hummingbirds are attracted to this color

-

Place feeders near flowering plants but away from windows to prevent collisions

-

Use a mixture of 4 parts water to 1 part white sugar; avoid honey or artificial sweeteners

-

Clean feeders thoroughly every few days to prevent the growth of harmful mold and bacteria

-

Consider placing multiple small feeders rather than one large feeder to reduce competition

Here’s a great article that tells everything you need to know about how to choose the best place to hang your hummingbird feeder.

Here’s a comprehensive guide to help you clean your hummingbird feeder for those times when the nectar is not changed soon enough and mold starts to grow.

Additional Garden Features

-

Provide a water source: A small fountain or dripper can attract hummingbirds for bathing and drinking

-

Offer perches: Small bare branches near feeding areas give hummingbirds a place to rest and survey their territory

-

Avoid pesticides: These can harm hummingbirds directly and reduce insect populations they rely on for protein

Frequently Asked Questions

How long do Allen’s Hummingbirds live?

Allen’s Hummingbirds typically live 3-5 years in the wild, though some individuals have been known to reach up to 8 years of age. Their small size makes them vulnerable to predators and environmental challenges, but their agility and speed help them survive.

Are Allen’s Hummingbirds endangered?

While not currently listed as endangered, Allen’s Hummingbirds are considered a species of special concern due to habitat loss and potential impacts of climate change. Conservation efforts are crucial to ensure their populations remain stable.

How fast can Allen’s Hummingbirds fly?

These agile birds can reach impressive speeds:

-

Normal flight: 30-40 mph

-

Dive speeds during courtship displays: up to 60 mph

-

Ability to hover and fly in all directions, including backwards

Do Allen’s Hummingbirds migrate?

The migratory subspecies (S. s. sasin) travels between breeding grounds in California and Oregon to wintering areas in Mexico. The sedentary subspecies (S. s. sedentarius) remains year-round on the Channel Islands and in parts of the Los Angeles basin.

How many times a day does an Allen’s Hummingbird eat?

Allen’s Hummingbirds feed frequently throughout the day, visiting hundreds of flowers. Their high metabolism requires them to consume about half their body weight in nectar daily, supplemented by small insects for protein.

Conclusion

Allen’s Hummingbird is a remarkable species that adds vibrancy and wonder to the coastal ecosystems of California and southern Oregon. Their iridescent plumage, acrobatic flight, and crucial role as pollinators make them a joy to observe and an important subject of conservation efforts.

As we’ve explored in this guide, these tiny birds face several challenges, from habitat loss to the impacts of climate change. However, through increased awareness, conservation initiatives, and individual actions like creating hummingbird-friendly gardens, we can help ensure that Allen’s Hummingbirds continue to thrive.

Whether you’re a dedicated birdwatcher, a nature enthusiast, or simply someone who appreciates the beauty of wildlife, keep an eye out for the distinctive flash of an Allen’s Hummingbird on your next outdoor adventure. By understanding and appreciating these fascinating creatures, we can all play a part in their conservation and enjoy the natural spectacle they provide for generations to come.

One of the best Hummingbird feeders that’s easy to take apart and clean is the HummZinger Ultra.

Aspects 12ozHummZinger UltraWith Nectar Guard.

TheHummZinger Ultra12oz Saucer Feeder is one of the best options for a hummingbird feeder that’s both easy to clean and maintain. This top-tier feeder features patented Nectar Guard tips—flexible membranes on the feeding ports that keep flying insects out while still allowing hummingbirds to feed freely. Plus, it comes with an integrated ant moat to prevent crawling insects from reaching the nectar, and the raised flower ports help divert rain, keeping the nectar fresh.

With a 12 oz capacity, this mid-size feeder offers plenty of space and can be hung or mounted on a post using the included hardware. It has four feeding ports and is made from durable, unbreakable polycarbonate. Whether you’re concerned about bees, wasps, or ants, this feeder is built for easy cleaning and insect protection.

If you already have a hummingbird feeder, and you want to protect it from ants and other crawling insects, the ant moat below will do the job.

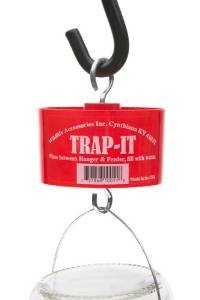

Trap-It Ant Moat for Hummingbird Feeders

Using an ant moat for your hummingbird feeder is an effective way to keep ants away from the sweet nectar. These tiny creatures are drawn to

the sugar water, and without a barrier, they will quickly infest your feeder, preventing the birds from enjoying the nectar. An ant moat works by creating a barrier of water that ants can’t cross. Positioned above the feeder, it effectively blocks the ants’ path, keeping them from reaching the nectar.

This simple solution also ensures that your hummingbird feeder remains clean and accessible for the birds, rather than becoming a breeding ground for ants or other pests. It’s a small addition that can make a big difference in maintaining a healthy, inviting space for hummingbirds, while also reducing the need for chemical ant deterrents.

The first and still the best toprotect your Hummingbird and Oriole feeder from ants and other crawling insects. Insert between hanger and feeder and fill with water, providing a barrier to crawling pests. Red color to attract hummingbirds.

| Smallbottle brushes and pipe cleaners are always helpful to dislodge mold inside the feeder and in the feeding ports. It is necessary to have a clean mold free feeder to attract hummingbirds and to keep them healthy. |

Use Songbird Essentials Nectar Aid Self Measuring Pitcher and never measure ingredients again. Make any amount and the ingredients are measured for you.

|

If you found this article helpful please share it with your friends using the social bookmarking buttons on the left side of this page. Help everyone to increase their enjoyment of feeding hummingbirds. Do it for the hummingbirds!

Hummingbird Resources

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Hummingbird Conservation

This site offers detailed information about various hummingbird species, their habitats, and conservation efforts. It also provides resources on how to protect these fascinating birds.

National Park Service – Hummingbird Resources

The National Park Service offers insights into hummingbird species found in national parks, their behaviors, and their role in ecosystems, along with tips for observing them.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History – Birds: Hummingbirds

This resource provides educational materials on the role of hummingbirds in pollination and biodiversity, backed by scientific research and exhibits from the Smithsonian.

U.S. Geological Survey – Hummingbird Studies

The USGS offers research on hummingbird migration patterns, population dynamics, and environmental threats, including studies on climate change impacts.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology – Hummingbirds

While not strictly a government site, Cornell partners with federal agencies to provide valuable scientific insights into hummingbird behavior, conservation, and field guides.